Disclaimer: I am not a scientist.

If you’ve watched my videos, you’ll know that one of the primary tethers that will keep me returning into towns is the need to charge up the various devices I plan to bring on my thru-hike attempt. No matter how deep my desire to immerse myself in nature, I’ll be using a headlamp, some wireless earbuds, a handheld GPS, and of course, the mack daddy of energy consumption, my cell phone. Even if I don’t use it as a cell phone every day, the device will also act as my journal, my map, my compass, my camera, my book, my music player, my calculator, and the list goes on. Like it or not, cell phones are incredibly useful outdoor equipment – no other single item I’ll be taking can do as many things, let alone as well as a phone can (sorry poncho tarp, I still love you).

In order to keep my devices powered, I’ll also be taking the Anker PowerCore Slim 10000 Power Bank. Whenever I venture into town, I’ll recharge my phone and this power bank, so that, in theory, I’ll be able to make it from one town to the next and keep all my devices charged.

With the exception of my headlamp, all of my devices have neat features that let you know exactly how much battery you have left before needing to be recharged. Sure, it may not uniformly be presented in terms of hours and minutes, but at least as a percentage, it’s a helpful barometer to gauge exactly how long that tether to electricity really is. The Power Bank, however, is a bit more primitive. It has four LED lights indicating current charge level – if all four are lit, you’re in the top quartile of juice, if three are lit, you’re in the third quartile, and so on.

This is useful, but as you may have experienced, can be problematic. There’s a pretty significant difference between the attitude that a 25% phone charge imparts as compared to a 3% charge. If the former, I’ll call the Uber, let’s hit the town! If the latter, I’m either going to have to stay home, or “go dark”. The Anker (and other power banks) doesn’t tell you this information. I’m OK with this since I don’t want my battery to be doing much else other than charging my devices, so something with more precision is probably more power draw than it’s worth.

Curious creature that I am, I set about to figure out a way to have a better sense on exactly how much battery capacity I had at any given time.

My first idea was to fully charge the power bank, and then use it to charge each of my devices exclusively until they die. From this, I could establish a percentage of the power bank that each item draws when charged, and then track the power bank in real time by subtracting the percentage drawn each time I charge a given device. For example, if the power bank is able to charge my phone four times, I’d assume the phone takes 25% of the bank’s capacity. I started experimenting with this approach using my AirPods. I quickly ran into a problem: a week later, having fully charged my AirPods four times, the Anker power bank still shows four LEDs (so somewhere between 75% and 100% remaining). At this rate, I wouldn’t have an answer before getting on the trail! I’m still convinced this method would prove effective if I had sufficient time to fully test all my devices, but here we are.

As noted above, the power bank I use is the Anker PowerCore Slim 10000. The “10000” in the name refers to the capacity of the battery – 10,000 milliamp-hours. Milliamp-hours (mAh) are a measure of current flow over time – any battery you use (or any device with a battery) will have a capacity that is measured in mAh. As I was trying to establish an expectation of how many times the power bank could potentially charge my AirPods, I found a website that claimed the AirPods Pro case battery has a 519 mAh capacity, and then each earbud has 43 additional mAh of capacity in their respective batteries (so 605 mAh total). My gears started turning… if the AirPods’ batteries are collectively full with 605 mAh, and my power bank has 10,000 mAh, then the power bank should be able to charge them 10,000 / 605 = 16.5 times, and each charge would take up ~6% of my power bank. Right?

Wrong. Here’s where we start getting deep. If I’ve already lost you at this point, I get it.

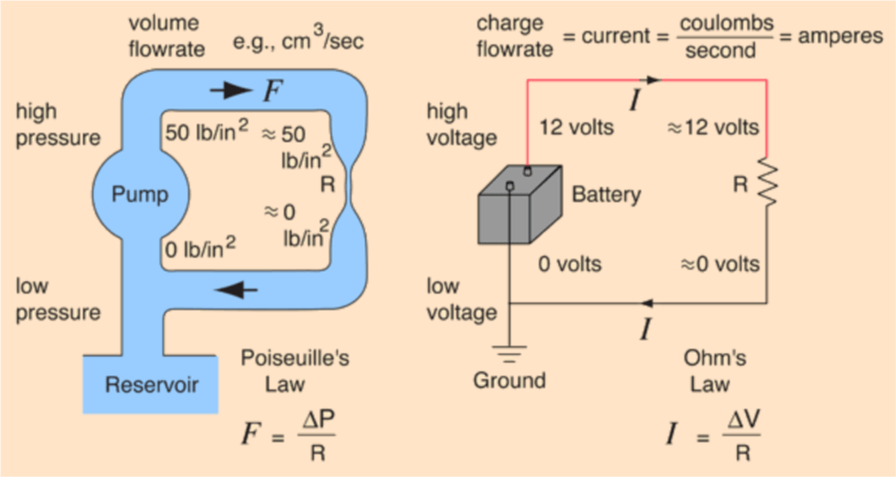

Let’s talk about volts. In plain English, volts are (physicist friends, you can roast me for this) the pressure from a power source that pushes electrons through a conductor. In SI base units, volts are expressed as kg*m2 *s-3 *A-1 . When you start having exponents greater than one (positive or negative) in a derived unit, I start having a really hard time understanding what it actually means. Fortunately, I’m not the only one with this shortcoming – there’s a well-defined analogy that addresses this, aiming to describe the relationship between volts, amps, and ohms (Ohm’s Law) in terms of a water pump.

Source: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/watcir.html#c2

So what does this have to do with our power bank conundrum? Well, your device battery has a varying voltage level while it’s being charged, but your power bank is providing 5 volts throughout the entirety of the charging process. For cell phones, the average voltage level whilst being charged is about 3.7 volts. This means that even though my power bank has 10,000 mAh of capacity, it can only actually provide 10,000 * (3.7 / 5) = 7,400 mAh to my cell phone. My iPhone 12 Pro has a 2,815 mAh capacity battery, so in theory, it ought to be able to charge my phone ~2.6 times (7,400 / 2,815).

What gives? You’re telling me they can sell me a 10,000 mAh battery that really only has 7,400 mAh? That should be false advertising! Not really. The issue is, different batteries that you’re looking to charge may have different average voltage levels whilst charging, so the math we did above may not apply across every device. So, even though it isn’t able to deliver all 10,000 mAh to the devices you charge it with, it would be equally (or perhaps more) incorrect to label it as 7,400mAh, because that’s the charge capacity that it can provide specifically to batteries whose average voltage during the charging process are 3.7V.

I then set about to get a better understanding of exactly what types of batteries are in the devices I’ll be charging during my thru-hike attempt. The 3.7V specification was in regards to smartphone batteries in general – Apple’s website shows 3.83V. For the sake of my estimation, I’m going to stick with the 3.7V, because it isn’t entirely clear to me that the advertised 3.83V is the measure that we’re after (average voltage during charging), and doing so is more conservative, anyway.

What about my other devices? From what I can tell, 3.7V is pretty standard for Lithium Ion batteries (perhaps the standard, but see the disclaimer at the top of the post), and it seems like all of my devices’ batteries charge at this average voltage level. This isn’t something that’s proved simple to get confident in – googling “what’s the average voltage during charging of the battery in a NiteCore NU-25 headlamp?” yields results that are at best confusing, and at worst, unhelpful. When voltage levels are presented, it’s difficult to determine if the voltage represents the average voltage during charging versus the maximum voltage (remembering from above that the voltage of the battery is going to increase as the device is being charged).

Further research yielded another wrinkle – even accounting for the differential in voltages between the power bank and the devices it needs to charge, there is an additional reduction in the actual capacity the power bank is able to deliver due to energy lost during the charging process. Different sources indicate this reduction is 10% – 15%, and the primary drivers of this inefficiency are twofold. First, because the power bank also has Lithium Ion batteries (that would like to have an average voltage of 3.7V), there is energy needed so that the power bank is able to output at 5V. Second, energy is lost through heat in the transfer from the power bank to the device.

With this in mind, let’s return to our calculation above. I estimate that for each of my devices, my power bank will actually be able to provide 10,000 * (3.7 / 5) * 0.85 = 6,290 mAh. For each device, then, I estimate:

- Apple iPhone 12 Pro (2,815 mAh capacity): 6,290 / 2,815 = ~2.2 charges, each charge uses ~45% of the power bank’s capacity

- Apple AirPods Pro (605 mAh capacity): 6,290 / 605 = ~10.4 charges, each charge uses ~10% of the power bank’s capacity

- Garmin inReach Mini (1,250 mAh capacity): 6,290 / 1,250 = ~5.0 charges, each charge uses ~20% of the power bank’s capacity

- NiteCore NU-25 Headlamp (610 mAh capacity): 6,290 / 610 = ~10.3 charges, each charge uses ~10% of the power bank’s capacity

Finally, the outside temperature has a material impact on Lithium Ion batteries and their ability to function. At the extreme ends of the temperature spectrum, battery performance is affected, although hot versus cold works in a different way. The net result, though, is stuff doesn’t work like you want it to. There are a number of resources that describe rules of thumb on how much temperature variations impact battery capacity, but I think trying to apply these rules of thumb in real-time isn’t going to add enough value to my “battery inventory” to be worth it. However, this is an important point to consider because I can control the temperature of the devices, to some extent. Even if it is freezing outside, my body will still be at or close to 98.6 degrees. So, when faced with cold temperatures, I will keep devices as close to my body as possible. At night, this will include sleeping with them in my quilt. When it’s super hot, I’ll aim to keep my devices tucked away in the shade of my backpack’s pockets.

Armed with the estimates above, I set out to test them. All of my devices aside from my cell phone present the same issue as my AirPods (that is, I don’t have sufficient time to exclusively charge them from the power bank and see how many charges I can get out of a fully charged power bank). This isn’t a bad thing, because it’s indicative of the fact that my cell phone is the primary device I need to be concerned with. The others require so much less capacity, or need to be charged so much less frequently, that their impact to my overall charging strategy isn’t all that important. Further, if I test my cell phone and discover that it’s above or below my expectation from the estimate above, it stands to reason that the ratio by which it differs from expected could by applied to the other devices.

Upon testing, I’m able to fully charge my cell phone 2.1x using the power bank. This is close enough to the estimate to be considered a success in my book!

So how will I use this information in practice? Well I mentioned at the top of the post my original idea was to keep a power bank inventory, but in reality, I’m not sure this is necessary. I will rarely plan to let my phone get all the way to 0% (since it’s a critical part of my navigation system), so based on the above, I think when I leave town with a fully charged phone and power bank, I should expect to be able to travel three phone charges before needing to re-up. This accounts for the fact that when I charge my phone, it won’t ever be from 0% to 100%, and I’ll need to charge my other devices along the way (but they all need charging much less frequently, and generally require substantially less power per minute of operation than the cell phone).

Neato.

Billy

Praying for you Will as you are walking each day to different areas. Have you ever read The Walk Series by Richard Paul Evans?

LikeLike

We love reading about charging devices with your battery bank. We are so glad that you planned to the degree that you did. It is who you are. I have a friend who lives in Brevard, North Carolina who has offered to meet you at one of your crossings and bring you supplies. I will tell him how to get in touch with you if you want me to.

LikeLike

That would be great! Thank you for thinking of me Uncle Richard!

Love y’all,

Billy

LikeLike